FYI from BSF, 12.3.21

Decline (Continued)

“Why is this happening?"

That was the most frequent question stemming from our enrollment analysisright before the Thanksgiving break. We were also happy to partner with our friends at Boston Indicators on a Massachusetts analysis, and turned around an even deeper dive into the Boston numbers.

The decline in the child population, and enrollment in Boston Public Schools, is most likely driven by multiple, complex factors, hard to disentangle and track.

So let's discount what is not causing these declines. What may seem like a possible or convenient explanation often is not held up by the data.

1. The pandemic did not create enrollment declines in Boston.

Enrollment decline began in 2015. There are larger, systemic forces that have driven down BPS enrollment; COVID-19 was just an accelerating factor.

2. Enrollment did not decline significantly everywhere else.

Statewide, public school enrollment for Massachusetts was largely unchanged from the previous year.

There are approximately 14 cities and towns that border Boston. Only one, Randolph, experienced sharp enrollment decline. The other 13 saw enrollment increases (like Chelsea, which in many ways was an epicenter for the pandemic) or were up or down by insignificant margins (like Revere or Milton).

There is also clearly not a “city effect” from last year. Behind Boston, the next 9 largest cities in Massachusetts saw a cumulative decline of only 0.7% over the past year. Boston’s 4% decline is significantly higher (and represents a lot more children, given its larger population).

3. Other school options did not create Boston’s enrollment declines.

Starting in 2010, with the Education Reform Act, charter enrollment began to increase, contributing initially to BPS enrollment declines. However, as charter enrollment has approached its cap and the pandemic began, charter enrollment has essentially flattened. Enrollment is significantly down in Horace Mann charters (charters that are authorized by the state but operate in Boston through a contract with BPS).

It is too early to ascertain the impact of private school enrollment this year, as that data is not released until the spring. But we know from last year’s data that even during the pandemic, private school enrollment for Boston children actually declined by more than 1,000 students since 2015. One note, this data does not include early childhood numbers for any schools, however, it is unlikely that private school enrollment is a significant factor.

4. Individual grades or an “off year” did not create enrollment declines.

The enrollment declines are diffuse across grades since 2015. Even exam schools aren’t full. Curiously, the bright spot of increased preK enrollment has not resulted in increases in kindergarten enrollment and beyond.

It is only worth interrogating this past data for the present and the future. With the city about to begin its annual, multi-billion dollar budget process, discussion should not focus on what has happened with enrollment, but on what does it mean for this year’s budget and future.

Will there be budget shortfalls this year? Unlikely. Despite the fact that the BPS budget is off by nearly 3,000 students, pledged municipal or federal stimulus funds can probably plug the hole (you can do the math yourself here).

This does come with a cost, however. As the city continues to fund schools based on student demographics and enrollment, schools’ empty seats are covered by “soft landings,” costing tens of millions of dollars per year.

It is true that Boston spends more per student than most communities in the country. It is also true that does not feel that way in schools, to leaders, educators, or families.

Failing to address these enrollment changes means more of the same: more and more money each year that feels like it is less and less.

Reopening Boston, MA and Beyond

On Wednesday, Boston School Committee met again with a full roster as Mayor Wu reappointed the two members whose terms had lapsed in the turnover from Acting Mayor Janey. Interviews are already underway for potentially two new members in January.

The biggest news again came during the Superintendent’s report with the announcement that three more schools will to expand to PK-6. Full materials here, including some demonstrated progress by the human capital department in recruitment, with an emphasis on educators of color. This is all the more impressive given the school labor shortages in some areas of the country.

Yesterday came the official news many Boston and Massachusetts families already knew - COVID cases amongst children and educators have skyrocketed.

Testing systems that were already under strain and under scrutiny are now under significantly more pressure. The upshot? Boston data is not public, but around the country other cities are reporting open schools but lower attendance, making the job of reacclimating students and educators that much more difficult.

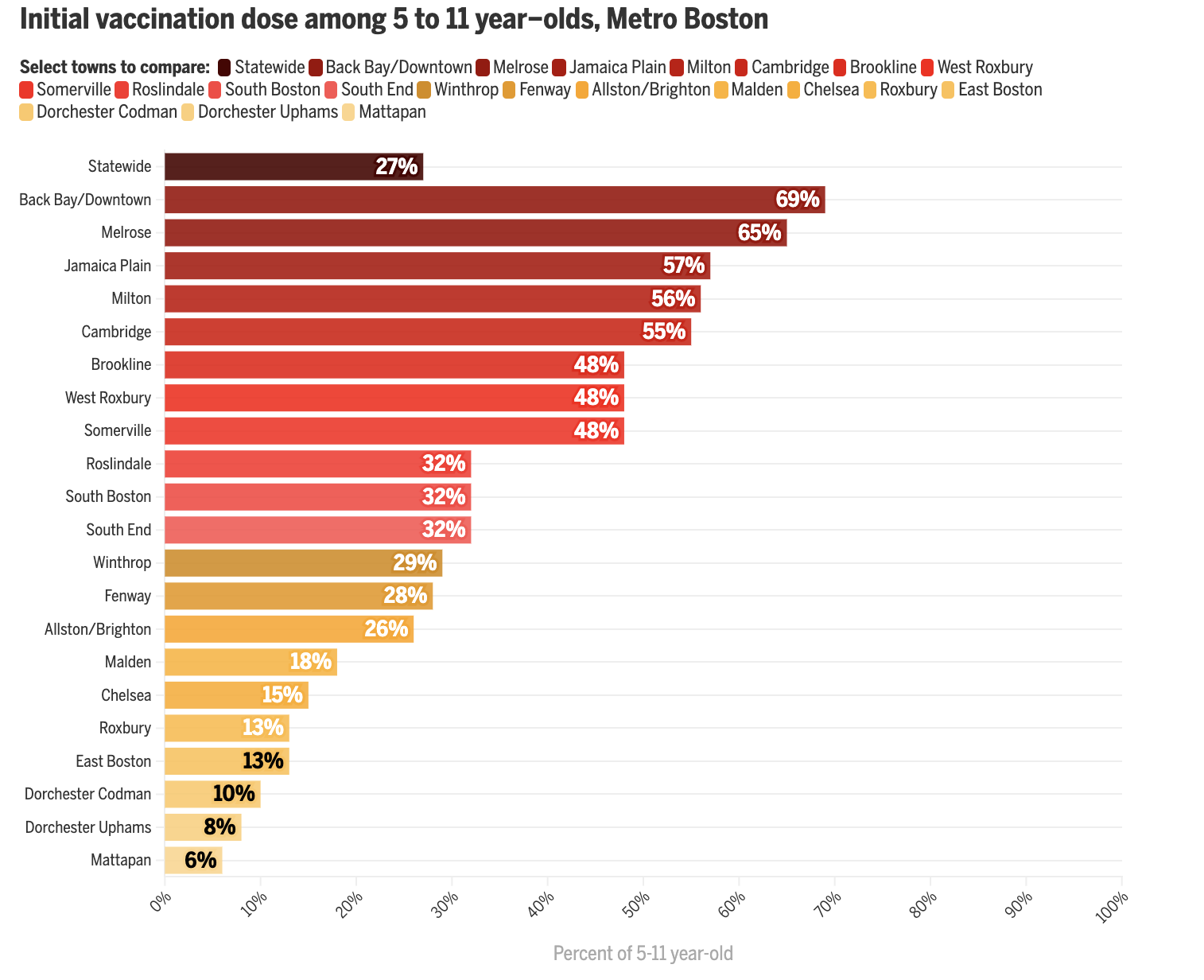

Can/will school districts respond in this new paradigm? It is likely harder in communities with a higher needs population. Some of the communities hardest hit by the pandemic are struggling the most to vaccinate children. Boston has added significantly more vaccine clinics, including many more in schools now. But Boston’s initial 5-11 vaccination rate of 23.3% lags well behind the state average, and features a massive racial access gap; in a segregated city like Boston, neighborhoods tell the story.

Other Matters

We should not look away from a painful fact: on Tuesday, it was statistically more dangerous to attend Oxford High School in Michigan than to attend the other ~130,0000 schools in America during a global pandemic. We are the only country on earth that allows school shootings to happen routinely.

Minneapolis, MN found its way into the spotlight twice this week. First, with a deep dive into school integration efforts there, and then with reporting that it will be using its federal funds to pay for its enrollment decline (while the other twin city, St. Paul, is closing schools).

Deep public and private investments in teacher evaluations do not appear to have paid off.

And, through all of this, educators persist.